We see things in Alejandra González Iñárritu’s The Revenant (2015) that we have not seen before and will not see again. This is not hyperbole; just consider the way the film was shot: out in the wilderness, under only natural light, where leading man Leonardo DiCaprio and the rest of the cast were perpetually in physical danger1. I wonder how much Iñárritu lied to or withheld information from the producers in order to get this film made, because the risks involved in shooting it seem too risky for your average production company like New Regency. Nevertheless, The Revenant is a mesmerizing and evocative film, and it’s a sure contender for this year’s Best Picture Oscar.

The plot of the film is paper-thin, but Emmanuel Lubezki’s astonishingcinematographyy and the film’s nearly three hour run time help you to forget this. Essentially, The Revenant is a revenge story, based loosely on the impossibly true story of 19th century frontiersman Hugh Glass. Glass is mauled by a bear early in the film—in a brutal scene that, in typical Iñárritu and Lubezki fashion, does not once cut (recall their enigmatic Birdman [2014], which seems never to cut)—and left for dead by his fellow trappers. While immobile and mute2, Glass witnesses his companion Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) murder his son, Hawk (Forrest Goodluck) when the latter spots the former attempting to kill the wounded man. Fitzgerald hides Hawk’s body and enacts a plan involving a lie about approaching “Ree Indians” (the Arikara) so that he will have a good reason to tell his superiors why he left Glass for dead in a shallow grave. The rest of the film follows Glass’s painstaking pursuit of Fitzgerald, which I want to stress again is roughly based on a real historical event3.

Though the plot is relatively straightforward, it occasionally dips into the metaphysical via hallucinations and dream sequences involving Glass’s murdered wife. People have criticized these moments as being disconnected from the rest of the film, but I can’t see the logic in this argument: if nothing else, The Revenant is a revenge story, so it makes perfect sense for us to see Glass constantly reminded of his murdered wife and son. They are the reason he is enduring, after all. Consider that before Fitzgerald murders Hawk, Glass essentially agrees to let Fitzgerald murder him; but after he watches the man knife his son, his will to survive strikes up because he now has a reason to live. Avenging his son—and, symbolically, his wife, who was also murdered by a white man—is what drives him forward; so it would indeed be odd if we didn’t have those dream sequences showing us that Glass is perpetually haunted by his murdered family. Critics too have questioned the relevance of the sub-plot involving Glass’s liberation of the Arikara girl from sexual enslavement to the French trappers. Without this moment, there wouldn’t be any reason for the Arikara to kill Fitzgerald and leave Glass alive in the closing moments of the film; with it, we’re given closure. Despite what the film’s detractors might argue, this film is not disjointed. There are no plot holes, due no doubt to the story’s simplicity, and even the odd metaphysical moments have relevance.

A word here on the Native Americans in The Revenant: they are not simply elements in the forces of nature; they are a force of nature. Throughout much of the film, they seem to be coming out of the trees and the earth. In the beginning attack sequence, they are barely visible until the scene is almost over; the only way that we are aware of the presence is through the death that suddenly appears: men go down with arrows mercilessly driven into their throats and other body parts, and though we, like the trappers, try frantically to find the attackers in the trees, they are too well concealed for us to really see. They literally seem to be a natural part of the landscape. Given that they are depicted as a force of nature, I’m perfectly content with their role in the ending. “Vengeance is in God’s hands,” Glass realizes as the film winds down; and so, he releases Fitzgerald downstream towards “God,” or as close to God as can be found on earth—nature, represented here by the natural force of the Arikara. The natives, a force of God, complete God’s vengeful work.

To say that Emmanuel Lubezki achieves the same level of cinematographic success that he did in Birdman and earlier in Gravity (2013) is a vast understatement: I mentioned earlier the mad decision to film The Revenant only in natural light; this, in conjunction with the frequent mobile long takes and the intimate nature of the shots (we see the condensation from DiCaprio’s breath layer the camera lens more than once) makes us feel as though we are there, as though these terrible things were happening to us. The bear-mauling scene is one continuous take, devoid of the cuts that help remind us it’s “not real;” Glass’s stealthy dip into the frigid river and his subsequent escape from the Arikara are likewise filmed continuously, and it feels to us as though we’re there in the hypothermic water.

Much has been made about this being the performance that will finally nab the Best Actor Oscar for DiCaprio. I certainly hope for his sake that he gets it. Warm feelings aside, he has earned it; if he wins, it won’t be a case of “He-wasn’t-that-good-but-for-God’s-sake-just-give-it-to-him-already!” Though Lubezki’s cinematography plays a major part in engrossing us in the film, we wouldn’t be wholly engrossed without DiCaprio’s performance. He gives it the last touch it needs to suspend our disbelief and make it feel real. When discussing the bear-mauling scene with my wife last night, I realized that it isn’t the bear that makes that scene so terrifying, nor is it just the continuous take; rather, it’s the continuous look at DiCaprio’s face and his reactions to the bear. His expressions don’t look like stock Hollywood reactions; he doesn’t stoically accept his fate, nor does he scream helplessly. Much to the contrary, his face is perpetually terrified and he legitimately seems to be suffering. You realize with horror upon watching this that this is what it looked like when Timothy Treadwell, the subject of Werner Herzog’s mesmerizing documentary Grizzly Man (2005), was eaten by an Alaskan Grizzly Bear in 2003. It is gutwrenching and nervewracking, but not superfluous, since it is the starting point of the narrative proper–and, of course, because it actually happened!

DiCaprio’s is not the only noteworthy performance. Tom Hardy is particularly effective as the squirrelly, wild-eyed (and partially scalped) Fitzgerald. One gets the feeling that any other actor would have made Fitzgerald a stock villain, contemptuous and violent; but Hardy’s mannerisms reveal depth–a genuine fear of the natives and a determined belief that wasting their time with the nearly dead Glass is bringing them all a step closer to being completely dead themselves. Domnhall Gleason4 gives us a terrific performance too, bringing a strong sense of humanity to what otherwise might have been the stock stoic military leader; like DiCaprio and Hardy, Gleason’s facial expressions reveal a subtly complex humanity beneath the battered surface of his skin.

Also of note here is the music, which like the performances, is subtly complex. It almost adds an element of a horror film to the movie, putting us on edge without overwhelming or distracting us. Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto’s score, while perhaps not deserving of the Best Original Score Oscar5, is effectively eerie and sets us in the right aural frame of mind.

The Revenant is not a film for everyone; my wife, for instance, will never watch all of it. The violence and brutality are simply too realistic and jarring. One walks away from this film feeling like he’s just watched a nearly three hour version of the Omaha Beach sequence of Saving Private Ryan. But those who can make it through the film will be treated to a cinematic experience unlike any that has been or will be. Like Glass is haunted by his memories of his family, so will you be haunted by your memories of this film. Iñárritu’s directing here is unparalleled–second perhaps only to Herzog’s infamous but brilliant directing on the set of Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), itself a blood-brother to The Revenant–the cinematography is genuinely idiosyncratic, and the acting is provacative. Even if you have to close your eyes during the particularly gruesome bits, see this movie now. It is a transcendent and transformative cinematic experience.

Footnotes

1Consider this article from Looper; Iñárritu filmed in some of the coldest and most formidable places on the planet. DiCaprio has said, “[I was] enduring freezing cold and possible hypothermia constantly.” He has certainly come a long way from being the whiny kid James Cameron made fun of for complaining about the cold water on the set of Titanic.

2Glass is rendered mute by the bear in one of the most disturbing moments of the film: after the bear saunters off momentarily to communicate with her cubs, Glass raises his rifle again and shoots her; furious, she bounds back and swiftly swipes Glass’s throat before flipping again into his back so she can proceed to tear at his spine. It’s not just seeing the almost casual swipe of the bear’s paw that is so horrifying; it is more so Glass’s reaction–clutching his throat and gurgling.

3In reality, Glass did not have a half-native son, though he did crawl two hundred miles out of a shallow grave after being mauled by a bear in pursuit of a man named Fitzgerald.

4Gleason had a busy and successful 2015: in addition to The Revenant, he was also impressive in The Force Awakens, Brooklyn, and Ex Machina—all noteworthy releases.

5This award ought to go to Ennio Morricone, whose classical “Morricone” score helps redeem Tarantino’s Hateful Eight of its disappointing mediocrity.

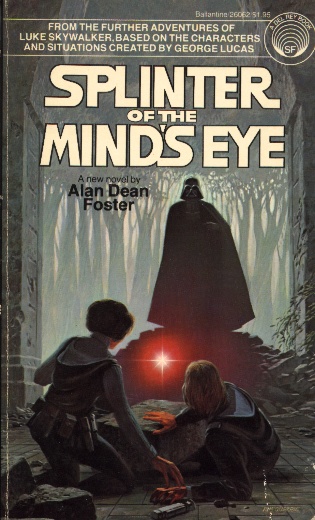

The storytelling of the Star Wars universe has a long and complex history. There are essentially two strains of stories at work: the jealously guarded “canon” (i.e., everything in the Star Wars films and the occasional external material) and the Expanded Universe (“EU”). The EU is older than most of the canon: Alan Dean Foster’s Splinter of the Mind’s Eye (1978) is officially non-canon due to odd elements in the book, like Princess Leia engaging Darth Vader in a lightsaber duel, but it was released before The Empire Strikes Back in 1980; so, the idea of telling Star Wars stories that don’t align with the “official vision” of the films has almost as long a history as the entire franchise itself.

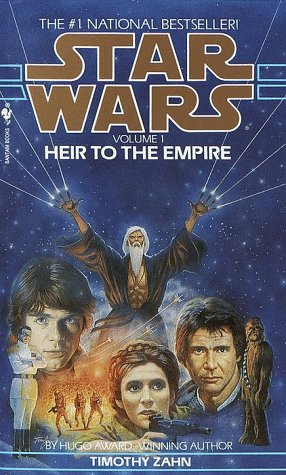

The storytelling of the Star Wars universe has a long and complex history. There are essentially two strains of stories at work: the jealously guarded “canon” (i.e., everything in the Star Wars films and the occasional external material) and the Expanded Universe (“EU”). The EU is older than most of the canon: Alan Dean Foster’s Splinter of the Mind’s Eye (1978) is officially non-canon due to odd elements in the book, like Princess Leia engaging Darth Vader in a lightsaber duel, but it was released before The Empire Strikes Back in 1980; so, the idea of telling Star Wars stories that don’t align with the “official vision” of the films has almost as long a history as the entire franchise itself. Personally, I’m happy with this reorganization. I read Zahn’s books as a kid, but when I realized that George Lucas didn’t necessarily approve or confirm everything in those books—and thus that, to me, the events and characters don’t really matter—I felt gipped out of the time I’d spent reading those books. Though certain elements from the EU have crept into the official Star Wars canon (such as the capital city-planet of Coruscant), much has since been proven false or only partially true. (For example, in the EU, starting with Zahn’s books, Leia and Han have twins, Jacen and Jaina, both who become Jedi, though Jacen eventually falls to the dark side; this has since been refuted by The Force Awakens, where it is revealed that Leia and Han [apparently] only had one child, Ben Solo, who—admittedly like Jacen—falls to the dark side.) After I realized that the EU was not authentic, I abandoned it for the most part.

Personally, I’m happy with this reorganization. I read Zahn’s books as a kid, but when I realized that George Lucas didn’t necessarily approve or confirm everything in those books—and thus that, to me, the events and characters don’t really matter—I felt gipped out of the time I’d spent reading those books. Though certain elements from the EU have crept into the official Star Wars canon (such as the capital city-planet of Coruscant), much has since been proven false or only partially true. (For example, in the EU, starting with Zahn’s books, Leia and Han have twins, Jacen and Jaina, both who become Jedi, though Jacen eventually falls to the dark side; this has since been refuted by The Force Awakens, where it is revealed that Leia and Han [apparently] only had one child, Ben Solo, who—admittedly like Jacen—falls to the dark side.) After I realized that the EU was not authentic, I abandoned it for the most part.